The Vikings coming ashore in America

In trees all over the world, scientists have found traces of a single solar storm. This lets us pinpoint the exact time a tree was cut down to build a house at L’Anse aux Meadows, in Newfoundland.

I heard of a silk shirt,

made across six lands.

One sleeve in Ireland,

the other far to the north in Finland.

Girls from Saxony began it,

it was woven in the Hebrides.

A Frankish woman wore it on her wedding day,

and it was woven on the loom of Óþjóðan’s mother.

(From Örvar-Odds Saga, 13th century.)

There is a grave at Cnip, in Lewis—a Viking woman’s grave. No one else was buried nearby. It wasn’t a cemetery, just sand and sea.

She lay there for a thousand years, buried with a comb, a knife, beads, and other items around her. And slowly, over time, all the memory of it disappeared.

No one now remembers who she was, what she looked like, what made her smile, or what she hoped to find in life.

But someone must have missed her at the time. Perhaps they buried her there and then left the island, watching the coastline fade behind them as they sailed north—to the Faroe Islands or to Iceland, maybe.

Or perhaps they returned to Norway. In her grave, archaeologists found a piece of cloth—a weaving pattern and technique that was common in Norway at that time.

There are a few references to the Hebrides in the Norse Eddas and sagas. Some even believe you can hear traces of Gaelic in the language of Iceland itself—that there are place-names which didn’t come from Norse, but from Gaelic.

It’s thought that the woman buried at Cnip lived in the 10th century. Now, evidence shows that another group of Norse people built a house for themselves in North America around that same time—in the year 1021. In my mind, there’s a connection between those people and their stories.

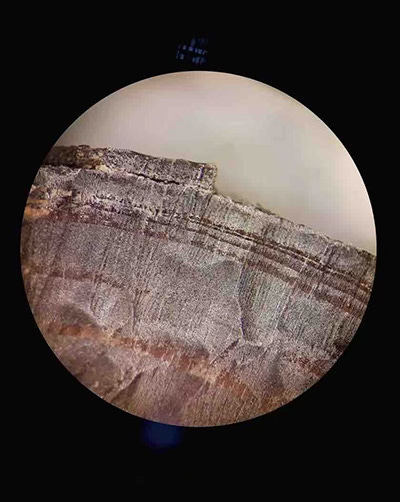

In trees all over the world, scientists have found traces of a single solar storm. This lets us pinpoint the exact season when a tree was cut down to build a house at L’Anse aux Meadows, in Newfoundland.

That’s what you’re looking at in this photograph.

(Photo by Petra Doeve, The New York Times.) You can read more about the science behind this discovery in Nature Magazine—I’ll leave a link at the end of the post.

We already knew the Norse reached America long before Columbus, but this evidence confirms when it happened. The story itself was already written down in two sagas (the Vinland sagas).

But even with this proof, it shows how hard it is to change a story once it’s taken hold of people’s minds. For example, that Columbus ‘discovered’ America.

It also shows a particular way of thinking about land—that Columbus could ‘discover’ a place where the Aztecs had already built cities long before he arrived. This is Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, in 1519.

How many of us know Thorstein, Aud, Erik, and Leif Eriksson as well as we know Columbus, Isabella, and Ferdinand?

But the evidence remains. The truth of the story rises to the surface eventually. It’s strange to think that events from a solar storm could leave such clear traces in the materials we use—in our houses, in our tools—and that we now have the understanding to make sense of it all.

It’s remarkable, really, to feel so close to those people. To know the exact year someone felled a tree to build a house at L’Anse aux Meadows, and everything that came with that moment—someone searching for a place, a home, warmth.

I think, in a similar way, you can hear echoes of Gaelic—of its people, its language and its placenames - running through this story too. This is the first part of the ‘Saga of Erik’.

SAGA OF ERIK (Part One)

There was once a king named Olaf the White, son of King Ingjald. Olaf went to Britain, where he took control of Dublin. He married Aud, daughter of Ketil Flatnose, and they had a son named Thorstein the Red.

Olaf was killed in Ireland, and then Thorstein and Aud travelled to the Hebrides in Scotland. Alongside Earl Sigurd, Thorstein took control of Caithness, Sutherland, Moray, and half of Argyll.

Thorstein was later killed when the Scots turned against him. Aud was in Caithness when she heard of his death.

She secretly built a ship in the middle of a forest, and when it was ready, she sailed to Orkney, and then to Iceland, with twenty men on board.

Many noble people from Britain, now enslaved, travelled with her to Iceland. One of them was a man named Vifil, whom Aud freed.

Erik the Red was the son of Thorvald and Aud. He married a woman named Thjodhild, and they had two sons—Thorstein and Leif.

And Leif Eriksson found a place no one had known before. There were fields of wild wheat, and grapevines, and among the trees were maple trees. The rivers were full of countless fish, and the forests full of animals of every kind.

They took samples of what they found. And they named the place Vinland.

You can see those connections appearing in words written long ago, in the time of the raiders. As the writer Stephen King once said, writing is a form of telepathy. In good writing, he says, you see exactly what the writer saw.

We can read the words of these people, and in them, we can see for ourselves how Gaelic is woven through everything in this story—just like it was woven through the piece of poetry I quoted at the start of this piece.

END.

You can read more about the science behind this in Nature Magazine:

IF YOU WOULD LIKE TO READ THIS POST IN SCOTTISH GAELIC, HERE IS A LINK.

Thank you for reading.